WHAT ARE THOSE BIG BLACK BEES?

By Chris Williams on April 29, 2019.

These bees are familiar, you think. Then you remember that they seem to show up every spring at about this time and in the same place, too. They’re pretty aggressive, noisy, and diving and swooping at you when you come near.

It may seem like there’s a whole hive of bees when they’re chasing you away, but you’re probably just seeing a pair, or maybe a couple of pairs, of carpenter bees. These solitary bees don’t even have a hive to go home to. They’re busy creating a tunnel-like nest site in wood around your home but they won’t live there. After the female provisions the nest with pollen and several of her eggs, the pair will move on.

Carpenter bees can sometimes leave the homeowner with a bit of a mess: slight wood damage that can be made much worse when woodpeckers discover the nest site. More on that later.

YOU’D HAVE TO WORK TO GET ONE TO STING YOU!

It’s the male bee that is harassing you because he is guarding the nest site from predators while the female works. He puts on a good show to keep you away, but he’s all bluff. To add to the threat, he buzzes loudly and may hover right in your face. But not to worry, he can’t hurt you because he doesn’t have a stinger, which is a modified female ovipositor, an organ for laying eggs.

Carpenter Bee. Shutterstock.

On a field trip, an entomology professor left students aghast when he snatched a passing carpenter bee out of the air, holding it buzzing in his hand. With a smile, he revealed the trick. He knew this was a stingless male carpenter bee because he saw a yellow blaze on its “forehead.”

The female carpenter bee doesn’t have the yellow facial marking. Otherwise, the two sexes look alike. We don’t recommend that you try this trick though unless you’re very sure because the female bee does have an ovipositor. She is reluctant to sting but will defend her nest if it’s directly threatened. It’s almost certain that the bee you see patrolling the nest site is a male.

These carpenter bees are our common eastern carpenter bees, Xylocopa virginica, which are large and black and yellow. There are western species of carpenter bees that are mostly dark or metallic in color.

CARPENTER BEE OR BUMBLE BEE?

If you are looking to avoid stings, it might be useful to know whether you are dealing with a carpenter bee or a bumble bee. The eastern carpenter bee can be easily confused with one of the larger bumble bee species. Both are quite large, almost 1 inch long, with a fuzzy yellow thorax and a black abdomen. The primary difference is that the top of the carpenter bee’s abdomen is hairless and shiny black, while the bumble bee has a fuzzy black and yellow abdomen.

Common Eastern Bumble Bee. Shutterstock.

The two bees may look similar but they have very different habits and lifecycles. As mentioned, carpenter bees are solitary bees that do not live in or work to support a hive of other bees. A single pair makes a nest site in weathered wood and generally goes about its business. Bumble bees, like honey bees, are social bees that live in a hive or colony in or on the ground. The workers are technically all sterile female bees so all have a stinger. Because it’s all about protection of the colony, a bumble bee will sting if it or the colony is threatened and it may recruit help from the colony as well.

CARPENTER BEES AREN’T AROUND FOR VERY LONG

Depending on location and weather, our carpenter bees emerge from their winter quarters in early spring. They mate and each pair begins nest construction and egg laying which occurs in late spring, April and May mainly. Most of the activity takes place over a two-week period.

Carpenter Bee starting a gallery hole. Shutterstock.

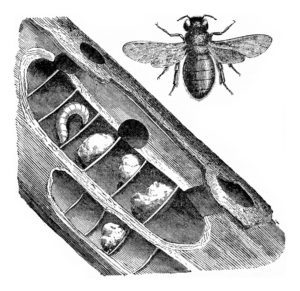

Once the carpenter bee pair chooses a nest site, the female works nonstop, first excavating the nest in the wood while the all-bluff male nearby acts as guard. Her goal is a gallery that is several inches long and will contain 6 to 8 individual larval cells, each separated by a partition. The entrance hole that she starts with is perfectly round and the exact diameter of her body, about dime-sized. This hole and perhaps some coarse sawdust is the only visible part of the nest. Once inside the wood, the gallery makes a sharp right-angle turn as she then follows the grain of the wood to construct brood cells.

Next step is to provision the nest with food for the young bees since mom won’t be around to feed them later. Starting at the back of her gallery tunnel, she places a ball of pollen and lays an egg on it, then seals the cell with a chewed wood partition. Then repeat for a total of 6 to 8 cells. The eggs will hatch into helpless tiny bee grubs, each confined in its own cell but with a ball of pollen for food left by mom. By the time that pollen is consumed after several weeks, the larva has grown to almost fill its space and then pupates inside its cell.

If you watch a pair during nest construction, you can likely figure out where the nest is located as you see the female coming and going. To actually see the round nest opening, however, may require contortions since it is almost always on the bottom or unpainted back side of a piece of wood.

Sometimes the female decides to rent instead of build anew. She takes a short cut and will lay eggs in an already existing gallery from the previous year, often extending it as she goes. Newly mated carpenter bees tend to build nests in the same location where they emerged. So, an especially desirable site with choice wood, can become an annual home to many pairs of nesting carpenter bees. That could be a problem.

Despite the nonstop nest building activity that goes on for several days, when it’s over, it’s over. Once the nest is completed with pollen balls in place, eggs laid, and brood cells sealed, the female seals the circular nest opening and the pair moves on, leaving few traces. Job done, the pair will die within a few weeks.

Just when you think you’ve seen the last of carpenter bees until maybe next spring, two things can happen: (1) as larvae develop inside their galleries through the summer, they may attract the attention of hungry woodpeckers, and (2) in late summer, bees that have been pupating in the nest (and have survived woodpeckers and other predators) finally chew their way out from the gallery, emerging as adult bees. These late summer adult bees aren’t into nest building. They will visit flowers and feed on pollen. If you see them entering a nest hole at this time of year, it’s because they are cleaning out the old galleries so they can use the protected nest as a place to spend the winter.

WHAT ABOUT THE DAMAGE TO MY HOUSE?

Carpenter bee damage can be significant but usually is not. One reason is that the wood attacked is often old, weathered and worn, or hidden so the damage is not obvious. Unlike other wood-damaging insects that can destroy structural timbers, carpenter bee damage is usually cosmetic, limited to trim boards or railings on homes. Many homeowners never even see the wood damage unless it becomes really obvious or someone points it out. Even then, all you see is a dime-sized entrance hole into the wood. Doesn’t look so bad. The real damage is the tunnel or tunnels that run lengthwise inside the wood.

Termites eat the wood; carpenter bees just chew through it for a limited distance. Of course, if the bees are chewing into expensive teak deck furniture or highly visible front porch railings, the damage becomes important to you. Damage is usually from a single bee pair, or two. But wood damage can be cumulative and more serious if you have several pairs of bees that are nesting in the same areas on your house or deck year after year.

Illustration of the internal workings of a Carpenter Bee Gallery. Shutterstock.

Since the carpenter bee female has to chew her brood tunnel into the wood, she prefers weathered or soft woods that are easier to work such as cedar, teak, redwood, pine, and fir. She also doesn’t want to chew through paint or shellac or any other covering on the wood, so she searches for unpainted or untreated, naked wood. This is one reason that entrance holes are usually hidden on the underside or back of a piece of wood.

Carpenter bee damage often occurs at the roofline where entrance holes are found on the usually unpainted backsides of fascia boards. Bees building a nest here are usually not even noticed. Other typical carpenter bee nest sites are: unpainted redwood or cedar deck boards or rails, the underside of outdoor wooden furniture, the back side of thick wooden siding or shingles, soffits, unpainted trim boards, mailbox posts, cedar posts, and unpainted windowsills.

Besides damage to wood, homeowners object to yellowish-brown drip stains on the siding of their homes beneath the nest site. The fastidious female bee defecates at the nest opening before she enters the gallery.

NOT FASCINATED BY CARPENTER BEES? THERE ARE OPTIONS

Like other bees, carpenter bees are beneficial insects that collect pollen and help to pollinate flowering plants. Control of carpenter bees is not usually necessary but should be considered if there is structural or unacceptable cosmetic damage to wood, if damage reoccurs year after year, if woodpeckers become an issue, or if someone is allergic to stings.

Carpenter bee nest building can be fascinating to some, but if you’re the homeowner, you may not much like the idea of galleries in your wood with bee larvae developing inside. Here’s the good news. If you’re not into watching carpenter bees build their nests in your deck, Colonial Pest can help with advice and control measures.

Painting susceptible wood is one of the best controls since the bees don’t like to chew through the surface. Replacing wood with PVC trim or railings, or wrapping fascia boards with vinyl or aluminum siding is a permanent control method. When you’ve had bees nesting in years before, Colonial Pest can treat the old nest sites early each spring before activity starts to kill overwintering bees as they emerge and to deter new nest activity. Nest sites under construction can be sprayed to kill the female bee. Completed nest galleries can also be injected with insecticide to kill larvae or new adult bees as they emerge in late summer.

HERE’S WHERE THE WOODPECKERS COME IN!

Shutterstock. Damage on fence related to Carpenter Bees.

Don’t be surprised if at some point later in the summer, after you’ve forgotten all about the carpenter bees, you hear enthusiastic hammering at the old bee nest site. Woodpeckers, you idly think, until you see that they are not just a-hammerin’, they are a-diggin’ into the wood with vigor.

Woodpeckers feed on insects found inside wood. Amazingly, woodpeckers can detect the presence of the fat bee larvae in their brood cells inside the piece of wood. While carpenter bees are not the only reason for this woodpecker behavior, it might be your first indication that there is a carpenter bee nest inside that piece of wood.

A full-grown carpenter bee larva looks like a legless, white grub. One larva is a nice meal for a woodpecker, two or more is a feast! After woodpeckers finish with a carpenter bee nest site, you may see a line of exploratory holes pecked in the wood, or deeper gouged and splintered holes directly above each brood cell where the grub or pupa was picked out. If you’re having the nest site treated to deter woodpeckers that are already attacking, that doesn’t always work. Unfortunately, once woodpeckers have discovered that food source, they may continue to peck away at the nest site for some time even after it’s been professionally treated to kill the larvae.

Good news though! Colonial Pest also specializes in nuisance wildlife management, and that includes woodpeckers that are causing problems. While woodpeckers are federally-protected birds, we can use certain deterrents to keep them away from where they’re not supposed to be. Bird netting or temporary sheathing can protect vulnerable wood until the birds lose interest.